Pricing case studies ask you to establish the amount that should be charged by a company for its goods or services. This might seem like a simple proposition compared to some other kinds of case, but pricing case studies can be just as knotty as any other problem your interviewer migth set. After all, if pricing cases weren't challenging, consultancies wouldn't give them, and many candidates fall down by applying overly-simple, generic approaches which fail in practice.

Pricing cases come up a lot. At the basic level, price is the benefit obtained by a company when they sell one unit of a good or service. Accordingly, it is imperative that companies choose the correct price for their products if they want to actually make a profit. However, the question of what this price should be is often complex, and it is one which consultants are frequently called upon to answer. Sinces cases will generally be based on real consulting engagements, problems around pricing are a recurring theme in case interviews.

Looking for an all-inclusive, peace of mind program?

Choose our mentoring programs to get access to all our resources, a customised study plan and a dedicated experienced MBB mentor Learn moreIn this article, we will provide you with a solid primer, letting you begin to tackle some pricing case studies. However, to be able to tackle more complex pricing cases (more like the ones you can expect in interview), the best resource will be our full length video lesson within the MCC Academy. There, the longer format gives us scope to drill down into details, with more mathematical sophistication and more worked examples to help you get to grips with how to actually apply theory.

What Determines Prices?

A primary reason for pricing case studies having the potential to be so complex is that prices are determined via the interaction of many different factors. Let's take a look at the main determinants of price:

1. Costs

Very simply, prices must cover a company's costs to break even and must more than cover costs for the company to turn a profit.

In some cases, where a company needs to lower its fixed costs but cannot do so immediately, they might offer a price which does not cover their total costs, but is sufficient to cover their variable costs.This means that the company will at least not lose more money as they sell more units of product.

2. Strategic Positioning

Companies will generally adopt a particular strategic position within their market. In doing so, they hope to achieve "competitive advantage" , which allows the company to make high levels of profit relative to the industry average. There are two fundamental ways to achieve competitive advantage:

2.1 Cost Advantage

Acompany enjoys a cost advantage by virtue of having a more efficient cost structure than competitors. Thus, the company is able to offer customers similar products to those from those competitors, but at lower prices. H&M, Primark and Zara are examples of fashion retailers whose low-cost production methods allow them to offer products at low prices, according them a cost advantage over competitors.

2.2 Benefit Advantage

In order to achieve a benefit advantage, a company must offer products which are better than, or otherwise differentiated from, those form competitors. This differentiation allows the company to charge higher prices than others in the market without losing out on sales. Hermes, Loro Piana, Kiton, Brioni and Drake's are fashion companies which offer products where higher prices are sustained by focus on high quality products.

3. Perceived Value

As we will learn below, in our discussion of value-based pricing strategies, value of a product as perceived by customers is crucial to optimal pricing. Customers have an idea of how much it would be reasonable to pay for a product, with this being quantified as an "expected price". Perceived value is fundamentally personal and different individuals will be willing to pay different prices for the same product. For instance, I might only be willing to pay $2 for a coffee, whilst someone else might be prepared to pay up to $7. However, nobody (well, nobody sane) will be willing to pay $500 for a coffee. Generally then, averages of value perceptions across a population provide very important benchmarks for pricing.

Join thousands of other candidates cracking cases like pros

At MyConsultingCoach we teach you how to solve cases like a consultant Get started4. Competitive Environment

It is a fundamental assumption that,where two products offer the exact same benefit to a customer, then that customer will prefer to purchase whichever has the lowest price. This makes a lot of sense - if you want to buy a certain book as a gift for a friend and it's available for $20 on Amazon and $10 on Ebay, then you'll probably buy it from Ebay.

However, the decision is not always as straightforward as this. Typically, perfect comparison (such as above, with identical books) will be impossible for a couple of reasons:

-

Product differences

One reason it can be difficult to compare options based on price is because the products on offer differ in their qualities, with it not being immediately obvious how much value those differences confer. For example, imagine that the book you are trying to buy is available in hardback for $20 from Amazon and in softback for $10 from Ebay. Is the extra $10 worth it for the nicer copy?

-

Imperfect Information

To make matters worse, you might also lack some information about the products you are comparing. Say you are looking at two pairs of jeans online. They're similar, but not identical. One looks a little nicer than the other, but is also more expensive - which should you chose? It's certainly far from clear without being able to see the products in real life - even then it might be difficult to tell which is better quality if the manufacturer has not made clear how the garment was constructed.

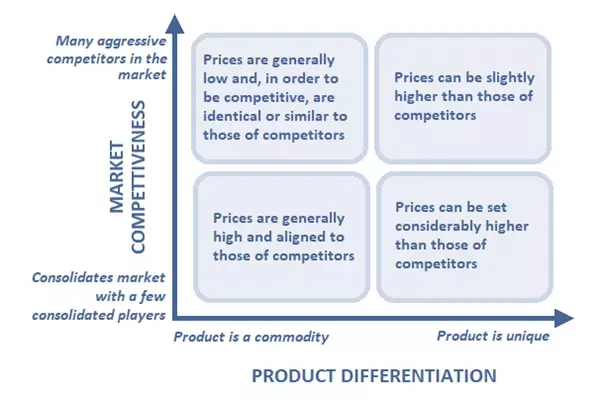

We can often interpret pricing as a combined function of the competitiveness of the market as a whole and the degree of differentiation of the particular product. The diagram below summarises the regularities we tend to observe:

5. Availability

Availability is a basic and well known driver of price. Generally, the more scarce something is, the higher prices will be. An old example is the different forms of carbon. Charcoal, graphite and diamond are all (at least largely) made up of identical carbon atoms in different arrangements. Despite all being made of the same thing, diamonds are more expensive than graphite, which is more expensive than charcoal. Indeed, this is true in spite of the fact that charcoal and graphite are more straightforwardly useful than diamonds, which will generally just be employed for ornamental purposes.

An AI-based, bespoke preparation plan

We’re all trying to get to the same place, but from different starting points. MCC automatically tailors your preparation to your own specific needs. Get started6. Market Trends

We are used to the idea of prices being affected by "trends" in the usual sense. Customers were probably willing to pay a lot more for an avocado-coloured bathroom suite or a pair of platform shoes in 1975 than in 2005. However, there are other market trends which together affect a broader range of product prices. These include:

-

Seasonality

Seasonal trends affect the prices of many products. For example, industries like hospitality and travel are highly dependent upon seasonality - we are all familiar with seeing the prices for hotels being discounted off-season or the cost of fights spiking around peak times, such as just before Christmas.

-

Product Life Cycle

Many products will lose value as they age. In particular, electronics typically see their prices fall rapidly as they get older. For example, a few months after a new model of phone is launched, it will already see reductions in price. These reductions will become even more severe after a couple of years when a new model is launched and our phone is no longer the current model.

Pricing Strategies

Consultants will often be employed to work out what price a company should charge for its products. This is absolutely crucial to get right. If the price is too low, the company will not make any profit and might go bust. If the price is too high, the company might not sell enough units to make a profit and - again - might go bust. This will often be the starting point for pricing case studies.

There are three standard approaches to pricing. Let's take a look at each in turn:

1. Cost-Based

Perhaps the most straightforward pricing strategy, cost-based pricing simply applies a standard mark-up above the company's costs. For example, a company might sell backpacks that cost $20 to make. They then simply apply a 25% mark-up and sell the backpacks for $25 each. The focus of the business is thus simply to make sure that they cover their costs.

Everything you need in one place

All the most up-to-date resources delivered as a MBA course Learn moreGenerally, cost based pricing strategies are a bad idea for businesses, as the prices generated ignore customers "willingness to pay". As such those prices are potentially much lower than they could have been - damaging profits. For instance, it might well be that our company's backpacks are particularly fashionable at the current time and that customers would be happy to pay $50 each for them. The company is losing out!

It is interesting to wonder how much something like a Gucci handbag might sell for if its price was determined under by a cost-based strategy. The price might be much more in line with those of similarly machine-stitched, mass produced bags from less high-profile producers and could be a fraction of the current amount. However, Gucci and similar brands obviously charge rather more than this. How, then, do they decide their prices?

2. Value-Based

In short, value-based pricing decides how much to charge for products, primarily as a function of customers' willingness to pay rather than the company's costs. The company aims to maximise profit by charging at or just below the value which the customer perceives a product to be worth.

The reason why fashion houses are able to attach such high mark-ups to certain products is ultimately because customers are willing to pay these prices to be associated with the relevant brand.

In order to estimate customers' willingness to pay, we first have to establish what the customers' "next best alternative" is. We then need to establish how our product differentiates itself from that alternative and then estimate how much customers would be willing to pay for those additional features.

For example, you might be selling smartphones of a roughly similar specification to others in the same section of the market, except that your phone's camera is of significantly higher quality. To work out your customers' willingness to pay, you must work out how much more someone would expect to pay for the increased camera quality you offer.

3. Competitive

In circumstances where competition is fierce and our product has a low potential for differentiation (such as a commodity), then we must not apply a higher price than our competitors if we want to remain competitive.

For example, if we are selling sand to the building trade, there is not much we can do to make our sand more appealing than sand from competitors. At the end of the day, sand is sand. In such cases, the price is more or less fixed by the market, so all we can do is to match, or be lower than, that market price. Our only option to increase profits is to pursue cost advantages.

Price Elasticity

The term "price elasticity" refers to what happens when we vary the price of a product which is already on the market. Generally, as we increase the price of a product, then sales will fall (with some exceptions).

There should be an optimal trade-off between price and sales which maximises a company's revenue. However, sales are unlikely to respond to changes in price in a simple, linear fashion. As such, working out the optimal price can be difficult and will often be something consulting firms are brought in to help with (and thus is something which is likely to come up in a case interview!). We discuss how this optimal pricing is accomplished and work through an example in our MCC Academy video lesson on pricing.

Next Steps

This article has provided a solid introduction to the key ideas in pricing and should be immediately useful as you practice pricing case studies. However, to understand the subject with the sophistication required by more demanding pricing case studies, your first port of call should be the pricing video in the Building Blocks section of the MCC Academy.

Otherwise, now that you have some understanding of pricing, we recommend that you go through our other articles on building blocks - including valuation, estimates, profitability and competitive interaction - so that you will be equipped to tackle this full set of recurring case interview themes!

Find out more in our case interview course

Ditch outdated guides and misleading frameworks and join the MCC Academy, the first comprehensive case interview course that teaches you how consultants approach case studies.